Last updated: December 29th, 2025 by Grant Fessler

- What is the Difference Between Savanna, Woodland, and Forest?

- Our Fire-starved Landscape

- Dry Woodland Association:

- Dry-mesic Woodland Association:

- Mesic Woodland Association:

- Mesic to Wet-mesic Alluvial Woodland Association:

- Dry and Dry-mesic Upland Forest Associations:

- Mesic Upland Forest Association:

Upland woodland and forest are best developed on river bluffs and in their associated ravine systems in the Quad Cities Region. Three subtypes of woodland and forest are recognized: upland, floodplain, and sand. The QC region contains all three subtypes, however, upland forest is perhaps the most widespread and common. Our region once supported extensive areas of fire-maintained savanna, but for reasons outlined below, that community type has become extremely rare and is no longer a defining feature of the landscape. Indeed, savanna is poorly understood in the QC region today.

What is the Difference Between Savanna, Woodland, and Forest?

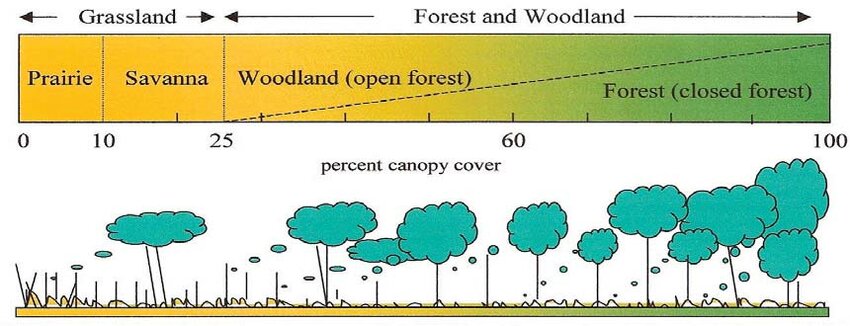

Savanna, woodland, and forest are related wooded community types that represent different points along a spectrum of fire frequency.

Savanna represents the tension zone between prairie and forest — it is a dynamic place where frequent fire supports a mix of trees and tallgrasses. Only the most fire tolerant trees such as Quercus alba, Quercus macrocarpa, and Quercus velutina can survive and are typically open-grown and widely spaced. Both prairie and woodland forbs and graminoids are present. Woodland can be conceived of as transitional between savanna and forest. These communities burned often enough to support a canopy of spreading-crowed oaks and a relatively open and park-like understory. Open oak woodlands contain a robust ground layer often dominated by species in the Asteraceae, Cyperaceae, Fabaceae, and Poaceae. Forest developed in places that burned the least frequently and least intensely, enough so that fire sensitive species like Acer saccharum and Tilia americana could thrive. Forests contain dense, multi-layered canopies and subcanopies composed of relatively straight trees with few lower or spreading limbs. The ground layer of remnant forests is composed of a diverse assemblage of shade-tolerant species.

Our Fire-starved Landscape

The Midwest is in the midst of a long period of landscape-level fire cessation which began in the early to mid 1800s with the removal of indigenous peoples. Increasing evidence supports the idea that indigenous cultures, not only in the Midwest but throughout much of North America, burned the land on an annual basis for various purposes including hunting, travel, and their food systems. This practice maintained prairie and savanna ecosystems here in the Midwest for thousands of years during the Holocene. In 1832, Black Hawk and his band of Sauk and Mesquaki peoples who resisted Euro-American settlement and land seizure by the US government, were defeated and forcibly removed from their homeland in present day Rock Island, IL. Immediately following this event, Euro-Americans settlers from the East flooded into what would become known as the Quad Cities region and Illinois, at large. With them, they brought their own set of land management practices which converted prairie, woodlands, and wetlands into farmland, roads, and settlements sensitive to wildfire. The extensive conversion of land to agriculture and policies of fire suppression implemented by the new inhabitants abruptly altered the time-honored rhythms of the landscape, sending a shockwave throughout the ecology of the Midwest.

One of the immediate effects of fire-cessation included the rapid growth of trees once subdued by the annual landscape fires. This caused virtually all savannas and open woodlands to convert to closed-canopied forest-like communities, if they were not cut or grazed. In fact, early settlers were astonished by the speed at which prairies grew up with trees in the first decades of Euro-American settlement. Fast forward nearly 200 years, and without annual fire, oak species, especially Quercus alba, Quercus macrocarpa, and Quercus velutina are rarely, if ever, recruited in our contemporary closed woodlands. Instead, a cohort of mesic, fire-sensitive species has filled the subcanopies and understories of virtually all upland woodlands. In presettlement times, these tree species would have been restricted to fire-protected landscape positions. In the QC Region, such species include Acer saccharum, Carya cordiformis, Celtis occidentalis, Quercus rubra, Tilia americana, and Ulmus americana. When woodland canopies close and light levels at the ground layer decrease, heliophilic (“sun-loving”) herbaceous species decline and eventually disappear, resulting in a depauperate, forest-like ground layer community with few, if any, species that bloom in summer and fall. Shade-tolerant species that now dominate the ground layer of many of our closed woodlands include Circaea canadensis, Cryptotaenia canadensis, Laportea canadensis, Parthenocissus quinquefolia, Sanicula odorata, and Toxicodendron radicans. Today, our best examples of open woodland are restricted to landscape positions most resistant to canopy-closure and forest conversion such as steep, dry, rocky south and west facing slopes and ridges. Species that once proliferated in the sun-dappled herbaceous layers of open woodlands and savannas are now relegated to woodland edges. In the QC Region, some of these species include Arnoglossum atriplicifolium, Eutrochium purpureum, Helianthus strumosus, Heliopsis helianthoides, Solidago ulmifolia, and Symphyotrichum shortii. With the disappearance of summer and fall blooming wildflowers under the oaks, our native insect communities which rely on the abundant nectar and pollen, especially of plants in the Asteraceae, have also declined. This effect, no doubt, has impacted our native bird populations many of which rely on healthy and abundant plant and insect communities in order to thrive. The widespread use of pesticides and herbicides starting in the 20th century has also exacerbated this issue and contributed to the degradation of our ecosystems.

The phenomenon of savanna and woodland conversion to forest-like communities would not be an issue if not for the fact that the native biodiversity of our region evolved throughout the Holocene with regular fire which maintained open, sunlit prairie and oak ecosystems. The dense, shaded, and fragmented forests of the 21st Century QC landscape are therefore without precedent, and they lack the biological memory needed to succeed into communities of the vigor and diversity known by their former phases.

Upland Woodland

Upland woodlands can be classified along a soil-moisture gradient from dry to wet-mesic. Dry-mesic woodland, however, is our most common and widespread type. Characteristic associations and discussion for each type are presented below. It is important to note that natural communities exist along a continuum and grade into each other, sometimes abruptly and sometimes very gradually. The associate lists below have been compiled from numerous examples of representative and relatively intact examples natural communities in the QC Region. There is some overlap in these lists, as certain species may be characteristic of two phases of a community type.

Dry Woodland Association:

Dry woodland is typically found on south and southwest facing slopes and ridges. Soils are relatively thin, usually rocky, and are excessively drained. The canopy is relatively open due to the relatively dry and drought-prone conditions.

The herbaceous layer of dry woodlands is characterized by Anemonella thalictroides, Antennaria plantaginifolia, Apocynum androsaemifolium, Asclepias quadrifolia, Bromus pubescens, Calystegia spithamaea, Carex cephalophora, Carex pensylvanica, Carex hirsutella, Danthonia spicata, Dichanthelium latifolium, Elymus hystrix, Helianthus strumosus, Hieracium scabrum, Krigia biflora, Lespedeza frutescens, Muhlenbergia sobolifera, Oxalis violacea, Potentilla simplex, Solidago ulmifolia, Symphyotrichum shortii, Symphyotrichum urophyllum, and Triosteum perfoliatum.

Quercus alba is the primary canopy tree and is often accompanied by Amelanchier arborea, Carya ovata, and Ostrya virginiana.

Dry-mesic Woodland Association:

This association is typically found on well-drained soils of slopes and level uplands where soils are deeper relative to drier sites. This community can grade into dry and mesic woodland.

The herbaceous layer of dry-mesic woodland is characterized by Agrimonia pubescens, Agrimonia gryposepala, Amphicarpaea bracteata, Anemonella thalictroides, Antenoron virginianum, Apocynum androsaemifolium, Botrypus virginianus, Bromus pubescens, Carex cephalophora, Carex hirtifolia, Carex pensylvanica, Carex rosea, Carya ovata, Carya tomentosa, Cinna arundinacea, Claytonia virginica, Dioscorea villosa, Elymus hystrix, Elymus villosus, Eutrochium purpureum, Festuca subverticillata, Fraxinus americana, Galium circaezans hypomalacum, Galium concinnum, Geranium maculatum, Hylodesmum glutinosum, Nabalus albus, Phryma leptostachya, Polygonatum biflorum, Prunus serotina, Quercus alba, Quercus macrocarpa, Quercus rubra, Quercus velutina, Ribes missouriense, Sanicula odorata, Scrophularia marilandica, Smilacina racemosa, Solidago ulmifolia, Symphyotrichum shortii, Trillium recurvatum, and Viola eriocarpa.

In more open situations, or more commonly on woodland edges, Anemone virginiana, Arnoglossum atriplicifolium, Dasistoma macrophylla, Desmodium cuspidatum, Desmodium glabellum, Desmodium perplexum, Dodecatheon meadia, Helianthus strumosus, Silene stellata, Triosteum aurantiacum, Triosteum perfoliatum, and Veronicastrum virginicum are characteristic.

The canopy is typically dominated by oaks such as Quercus alba, Quercus macrocarpa, Quercus rubra, and Quercus velutina. Hickories, such as Carya ovata and Carya tomentosa are also characteristic associates. Other common tree species include Fraxinus americana, Ostrya virginiana, and Prunus serotina. In many of our most mature examples of this association, however, Quercus alba is the dominant tree species.

Mesic Woodland Association:

Mesic woodlands are found on moderately well-drained soils of slopes and level ground including stream terraces. There may be great similarity in composition between mesic woodland and mesic forest, thus making their differentiation challenging. These communities were likely the first to convert to forests after fire suppression began after the Black Hawk War in 1832. See the Forest section for further discussion. As outlined here, mesic woodlands are distinguished by their fire-tolerant dominant canopy species and landscape position which were fire-prone in pre-settlement times. This community often grades into dry-mesic woodland, mesic forest, and wet-mesic woodland.

Herbaceous taxa characteristic of mesic woodlands include Actaea pachypoda, Adiantum pedatum, Agastache nepetoides, Agastache scrophulariifolia, Allium burdickii, Amphicarpaea bracteata var. comosa, Asarum canadense var. reflexum, Asclepias exaltata, Aralia nudicaulis, Aralia racemosa, Arisaema triphyllum, Athyrium angustum, Blephilia hirsuta, Brachyelytrum erectum, Cardamine concatenata, Campanulastrum americanum, Carex albursina, Carex copulata, Carex hirtifolia, Carex hitchcochiana, Carex jamesii, Carex oligocarpa, Carex rosea, Carex sparganioides, Caulophyllum thalictroides, Cinna arundinacea, Circaea canadensis, Claytonia virginica, Cryptotaenia canadensis, Cystopteris protrusa, Diarrhena obovata, Dicentra cucullaria, Dicentra canadensis, Dryopteris carthusiana, Elymus riparius, Elymus villosus, Enemion biternatum, Erythronium albidum, Eutrochium purpureum, Festuca subverticillata, Galearis spectabilis, Galium triflorum, Geranium maculatum, Hepatica acutiloba, Hydrophyllum appendiculatum, Hydrophyllum virginianum, Hylodesmum glutinosum, Impatiens pallida, Lactuca floridana, Laportea canadensis, Leersia virginica, Menispermum canadense, Osmorhiza claytonii, Osmorhiza longistylis, Osmunda claytoniana, Panax quinquefolius, Phlox divaricata, Podophyllum peltatum, Polygonatum biflorum, Polystichum acrostichoides, Sanguinaria canadensis, Sanicula canadensis, Sanicula odorata, Scutellaria ovata, Silene stellata, Solidago flexicaulis, Solidago ulmifolia, Symphyotrichum cordifolium, Symphyotrichum shortii, Trillium recurvatum, Uvularia grandiflora, Viola eriocarpa, and Viola sororia. Some of the most consistent ground layer species in mesic woodlands, however, include Adiantum pedatum, Asarum canadense reflexum, Athyrium angustum, Carex albursina, Carex jamesii, Cystopteris protrusa, Hepatica acutiloba, Hydrophyllum virginianum, Solidago flexicaulis, and Uvularia grandiflora.

The canopy may be composed of a variety of tree species including Acer saccharum, Carya cordiformis, Carya ovata, Fraxinus americana, Ostrya virginiana, Quercus alba, Quercus macrocarpa, Quercus rubra, and Tilia americana. Shrubs such as Cornus alternifolia, Corylus americana, Staphylea trifolia, and Viburnum lentago are characteristic.

Mesic to Wet-mesic Alluvial Woodland Association:

Contemporary mesic to wet-mesic alluvial woodlands are common on stream terraces in the QC region. These wooded communities typically display an open to somewhat open canopy and contain a characteristic association of plants. They often grade into mesic upland woodland and forest as well as floodplain communities. They are distinguished from floodplain communities by their high position that does not regularly flood. Seeps are often associated with these woodland communities due to their position near slope bases.

Common herbaceous species of mesic to wet-mesic woodlands on stream terraces include Amphicarpaea bracteata var. comosa, Asarum canadense, Chaerophyllum procumbens, Cinna arundinacea, Cryptotaenia canadensis, Elymus riparius, Hydrophyllum virginianum, Impatiens capensis, Laportea canadensis, Leersia virginica, Osmorhiza longistylis, Phlox divaricata, Pilea pumila, Ranunculus septentrionalis, Rudbeckia laciniata, Solidago gigantea, Urtica gracilis, and Verbesina alternifolia.

Tree species characteristic of these communities include Carya cordiformis, Celtis occidentalis, Juglans nigra, Quercus macrocarpa, and Ulmus americana. The shrub Sambucus canadensis may be common.

Upland Forest

In the QC Region, upland forest is best developed on the dissected topography found along the Mississippi River and its tributaries. In particular, north-facing bluff slopes and steep, rocky ravines are characteristic places to find upland forest communities. These places on the landscape likely burned relatively infrequently and/or with little intensity when indigenous peoples annually set the land ablaze prior to European settlement. These niches provided a refugia for fire sensitive trees species such as Acer saccharum, Asimina triloba, Carpinus caroliniana, and Tilia americana. Upland forests range from dry to mesic. Our best intact examples in the QC region are typically mesic forests located on rough, steep terrain that is challenging to access or develop.

Dry and Dry-mesic Upland Forest Associations:

Both dry and dry-mesic forest associations are very similar to dry and dry-mesic woodlands, and the terms “closed-canopied woodlands” and “forest” indeed may be used interchangeably when discussing these types of communities. Dry and dry-mesic forest are characterized by a forest structure (see discussion on this above in What is the Difference Between Savanna, Woodland, and Forest?) and a depauperate herbaceous layer dominated by shade-tolerant species. They are found in similar landscape positions to the woodland types. Many forests that developed post-settlement without a relationship to fire can be considered upland forests, as well. They are often less diverse and contain a more depauperate herbaceous layer than remnant open woodlands and remnant mesic forests.

Mesic Upland Forest Association:

As mentioned in the mesic woodland section, there is much similarity in composition with mesic forest. Remnant mesic forests in the QC region, however, are dominated by old-growth Acer saccharum, Tilia americana, and Quercus rubra and often contain other fire sensitive trees such as Asimina triloba and Carpinus caroliniana. Additional canopy associates include Carya cordiformis, Fraxinus americana, Fraxinus quadrangulata, Ostrya virginiana, and Ulmus americana. The herbaceous layer typically includes a diversity of spring-blooming plants, shade-tolerant forbs, sedges, and ferns. Examples of remnant mesic forest are no less diverse than any other remnant communities.

See the mesic woodland association for typical species of mesic forests. Note that in many instances, ferns are a dominant feature of the ground layer.

References

Fralish, James S.; Anderson, Roger C.; Ebinger, John E.; Szafoni, Robert. Proceedings of the North American Conference on Savannas and Barrens: Living on the Edge. U.S. Environmental Protection Agency, Great Lakes National Program Office.

Illinois Department of Natural Resources. 2023. Illinois Natural Areas Inventory Standards and Guidelines (revised edition). Springfield, Illinois. 105 pp.

McClain, William E.; Ruffner, Charles M.; Ebinger, John E.; Spyreas, Greg. “Patterns of Anthropogenic Fire within the Midwestern Tallgrass Prairie 1673–1905: Evidence from Written Accounts,” Natural Areas Journal, 41(4), 283-300, (18 October 2021)

Nowacki, Gregory J.; Abrams, Marc D. 2008. The demise of fire and “mesophication” of forests in the eastern United States. BioScience. 58(2): 123-138.

Wilhelm, G. & Rericha, L. 2017. Flora of the Chicago Region: A Floristic and Ecological Synthesis. Indiana Academy of Sciences, Indianapolis.